Author: Charles Musselwhite, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, UK

Every single journey begins as a pedestrian

I begin my book for Emerald, on designing public space for an ageing population[i], addressing how we improve pedestrian mobility for ourselves as we age and enter later life, with an important but often forgotten premise, “Every single journey begins as a pedestrian. Yet being a pedestrian is poorly conceptualised, often overlooked and misunderstood.” I go on to explore how the term pedestrian is often associated with something being unnecessarily slow or hampering. However, I argue this is a misconception. Being slow can add depth and colour to our lives. Rebecca Solnit (2001)[ii] reminds us of the Aristotelian school in Ancient Greece, and the Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge, taking their long countryside walks to inspire and influence their writing. It helps create connection at a local level, fostering what Bourdieu calls social capital[iii], knowing your neighbours, supporting one another, creating an environment where people help one another, linking people with their neighbourhoods and creating communities. If our pedestrian environment isn’t fit for purpose, we risk losing the bonds with where we live, potentially increasing isolation and loneliness. The famous study by Donald Appleyard and Mark Lintel[iv] of San Francisco in the early 1970s showed how traffic from private motor vehicles can impact on connections. They found that people on a street with busy traffic didn’t know their neighbours and retreated to the back of their home to do their living, those with lower amount of traffic knew more people, had kids playing on the streets and so forth. One street, with a low amount of traffic, had high social capital where people practically and emotionally look after one another, the other, with a high amount of traffic, none.

Walking is good for you:

Above and beyond that walking is good for older people’s physical health[v]. Regular walking or cycling can reduce cardiovascular disease by around 30% and reduce all-cause mortality by 20%, through reducing the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. It also keeps the musculoskeletal system healthy, keeps joints flexible, improves balance and coordination and can reduce potential for falls.

Older people talk about how important walking is for their mental health too. Research I have carried out supports that with older people for example saying,

“The walking makes me feel better I suppose. I feel less stiff and even though I might feel tired afterwards I feel sort of refreshed. I don’t feel that driving, I always got stressed about parking and the traffic and it became such a worry” (female, walker, aged 80; Musselwhite, 2018)[vi]

“you can go for a walk and if you’re not too worried about getting lost you discover places you didn’t know existed” (male, given up driving at 80, interview; Musselwhite & Haddad, 2010).[vii]

Conceptualising barriers

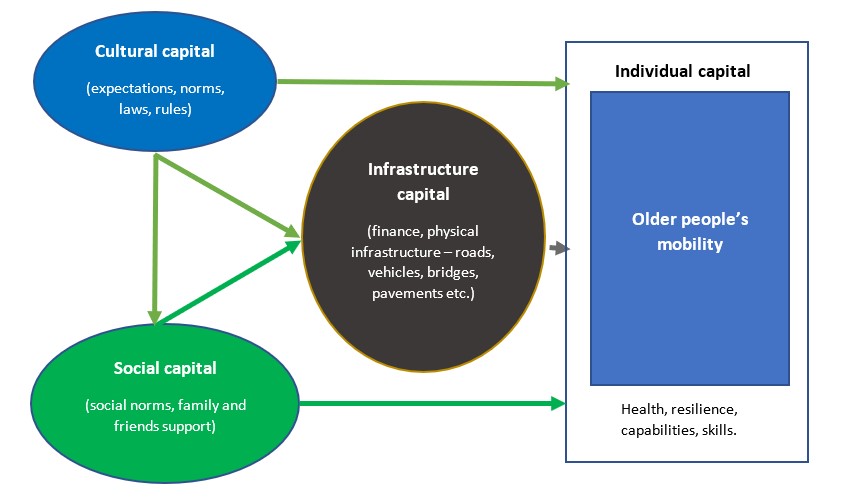

Yet there are so many barriers to walking. In the book I attempt to categorise the factors that affect walking around a theory of mobility capital devised by myself and Theresa Scott from the University of Queensland, Australia. Mobility capital[viii] is a resource we have to help us be mobile comprising of infrastructure, social, cultural and individual capital.

- Infrastructural enablers for walking include creating decent pavements, that are clutter free and well upkept, allowing space and time to cross the roads, enough lighting, enough seating and benches to enable comfortable walking,

- Individual capital, the abilities and skills the older person possess to navigate mobility, including physiology, for example eyesight, hearing, gait, physical fitness etc.

- Social capital allows space for people to meet and interact and be together without feeling hurried, and allow connections to foster.

- Cultural is the institutional support and governance that walking receives. The book suggests a complete change of heart and minds, a change of attitude and values around walking is needed, we need to stop seeing walking as something as a last resort, strategy, investment of resource needs to focus on improving pedestrians’ lives.

These capitals all of which may appear in different amounts at different times, with one capital plugging a deficit in another (for example where infrastructure capital is low, poor pavements, no places to cross, but social capital is high, mobility may still take place, for example older people might draw on social capital and get help to cross the road from someone more able to do so.)

Improvements that need to be made:

I conclude with recommendations for improvements in enabling more older people to walk:

Improving the safety and accessibility of the space (keeping vehicle speeds down, having dedicated and continuous, well-maintained pavements, that are clutter free. Having benches and toilets placed on key routes. Having good facilities for crossing the road).

Example: Street clutter can cause obstructions for older people when walking, West Cross, Swansea, UK.

Improving the legibility of the space (readable streetscape for pedestrians, with maps and signage, allow enough space for older people to navigate them and other users, thinking about how people use building to navigate).

Example: The pedestrian maps in Bath, in keeping with the heritage background, also pedestrian friendly, so have key buildings on them, are “heads-up” (face the way they are looking), rather than being North represented at the top, and concentric rings to show how long it would take to walk to places.

Improve the space to be distinctive and aesthetically pleasing (including keeping streets attractive through use of shelter, vegetation, water, colours and creating mystery and intrigue to encourage use and keeping spaces playful. Also exploring how local people may take ownership and control over the look and feel of their local walkways and pavements).

Example: A water feature in a public space, playful and cooling for all ages. Nice, France.

To conclude, we mustn’t forget walking

Overall, though, there is no doubt that the research I have uncovered on the topic suggests walking gets forgotten about. Its seen as up to the individual to fulfil, as just something that happens, what is left over once we have provided for mobility in other modes. This view needs to change to ensure people stay connected to the things they love doing in local communities and neighbourhoods that are rich and diverse and full of people, opportunity and resource.

Book: Designing Public Space for an Ageing Population: Improving Pedestrian Mobility for Older People

[i] Musselwhite, C. (2012) Designing Public Space for an Ageing Population: Improving Pedestrian Mobility for Older People. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

[ii] Solnit, R. (2001) Wanderlust: A History of Walking. London: Verso.

[iii] Bourdieu, P. (1986), ‘The Forms of Capital’, in Richardson, J.G. ed., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, New York: Greenwood.

[iv] Appleyard, D. and Lintell, M. (1970) Environmental quality of city streets. Berkeley: Institute of Urban & Regional Development.

[v] NICE Guidelines (2012) Physical activity: walking and cycling: Public health guideline [PH41]. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph41[vi] Musselwhite C. (2018) Mobility in Later Life and Wellbeing. In: Friman M., Ettema D., Olsson L.E. (eds) Quality of Life and Daily Travel. Applying Quality of Life Research (Best Practices). Springer: Cham.

[vii] Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2012) Mobility, accessibility and quality of later life, Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 25-37.

[viii] Musselwhite, C. and Scott, T. (2019) Developing A Model of Mobility Capital for An Ageing Population, International journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 16 No. 18. Available at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183327